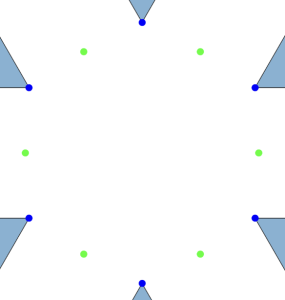

A few months ago, I encountered an interesting problem related to molecular crystallization. Consider a two-dimensional system with two types of molecules: the first type consists of rigid triangles with positive charges localized at the vertices (shown as blue triangles in the image below), and the second type is a single-atom molecule with a negative charge (shown as a green dot).

Our key questions are:

- Does this molecular system crystallize in the thermodynamic limit?

- If so, what are the characteristics of its ground states?

Let’s assume the system’s intermolecular interactions follow a normalized Coulomb/electrostatic potential:

![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() denote molecules of either type (green negative or blue positive triangular),

denote molecules of either type (green negative or blue positive triangular), ![]() is the Euclidean distance between charges

is the Euclidean distance between charges ![]() and

and ![]() . For green particles,

. For green particles, ![]() , while for vertices of blue triangles,

, while for vertices of blue triangles, ![]() . This creates attractive forces between opposite charges and repulsive forces between like charges, proportional to their relative distance.

. This creates attractive forces between opposite charges and repulsive forces between like charges, proportional to their relative distance.

The intermolecular energy is defined as the sum of all pairwise interactions ![]() between molecules

between molecules ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

![]()

This quantity generally lacks an infimum, so we need additional constraints.

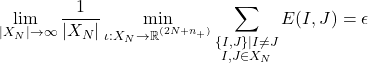

We aim to find a sequence of molecular configurations ![]() where the following limit converges to a constant:

where the following limit converges to a constant:

Here, ![]() represents a collection of

represents a collection of ![]() molecules of both types (

molecules of both types (![]() ).

).

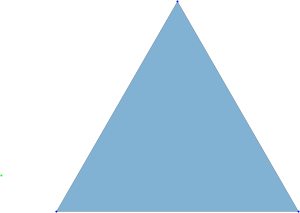

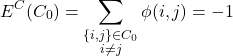

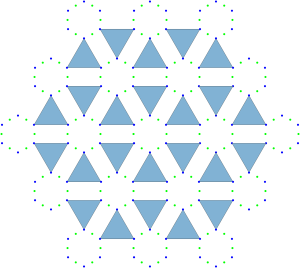

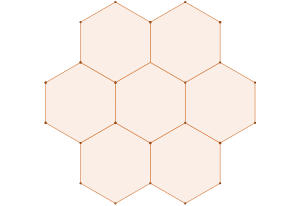

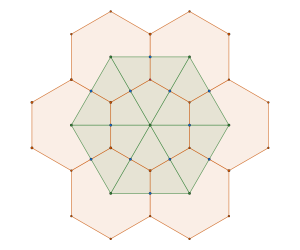

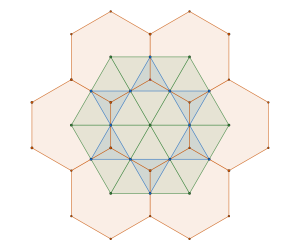

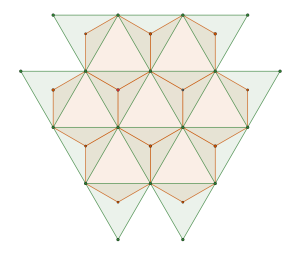

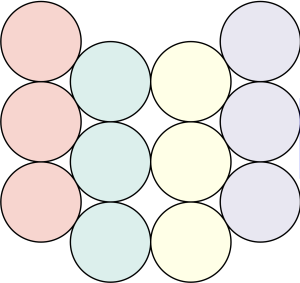

Let’s focus on local clusters, as shown below:

For any ![]() where

where ![]() , an alternating configuration of charges in a local cluster can found for any

, an alternating configuration of charges in a local cluster can found for any ![]() . Moreover, due to the rigidity of triangular molecules and the form of the potential

. Moreover, due to the rigidity of triangular molecules and the form of the potential ![]() , the maximal cluster contains

, the maximal cluster contains ![]() charges.

charges.

In our example cluster, ![]() , we set the energy to:

, we set the energy to:

for demonstration purposes.

Alternatively, the cluster configuration can be expressed in the form of the optimization problem:

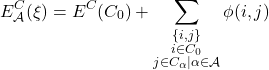

![]()

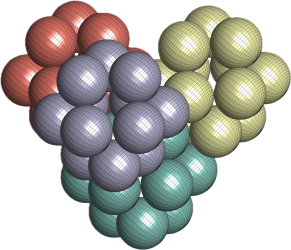

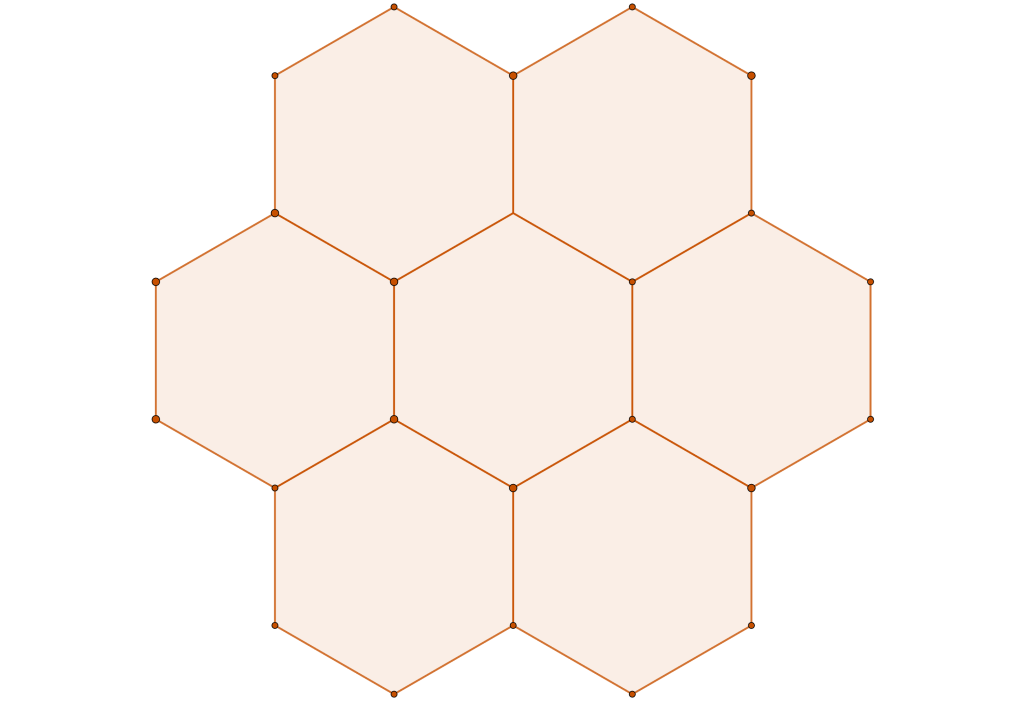

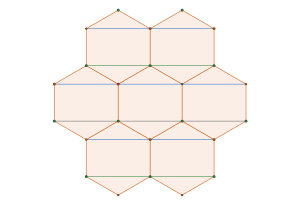

In the ![]() configuration, the blue positive charges occupy the interstitial voids of the hexagonal close-packed arrangement of negative green charges:

configuration, the blue positive charges occupy the interstitial voids of the hexagonal close-packed arrangement of negative green charges:

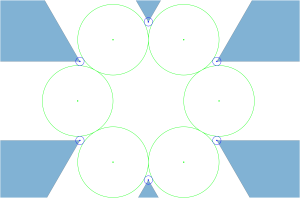

Following these local optimizations, we define a quantity we call the energy per cluster as:

where ![]() is an index set . Minimizing

is an index set . Minimizing ![]() for such a cluster collection becomes a well-defined problem:

for such a cluster collection becomes a well-defined problem:

![]()

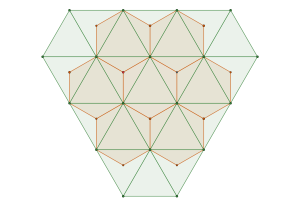

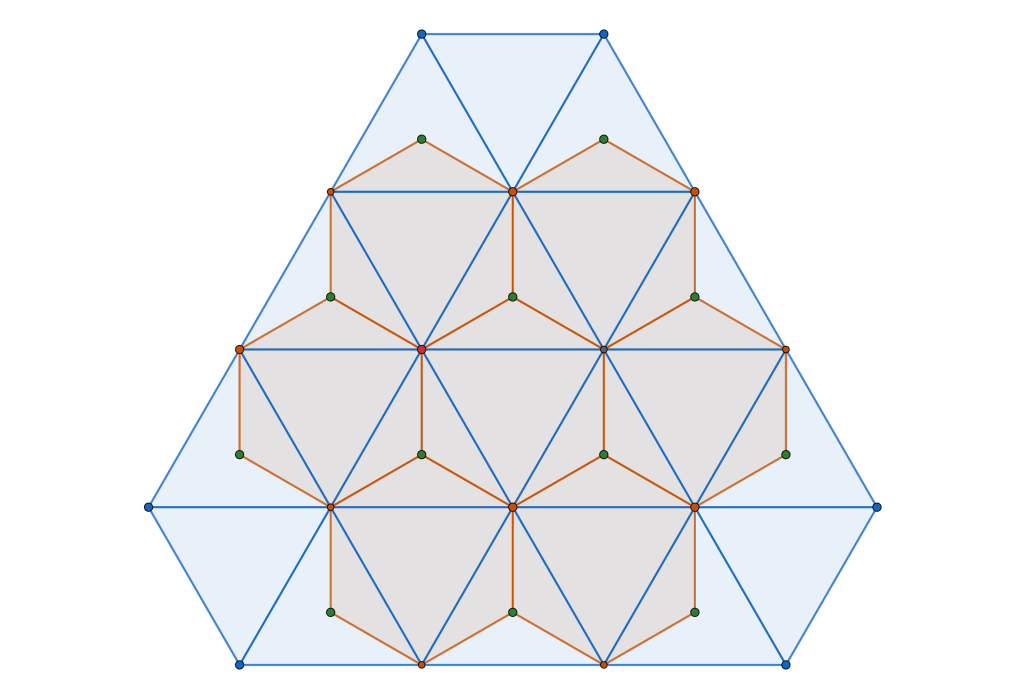

For cardinality ![]() , the solution is illustrated below.

, the solution is illustrated below.

Note that the interaction potential ![]() respects molecular memberships—for

respects molecular memberships—for ![]() and

and ![]() , we require

, we require ![]() .

.

We can expand ![]() to

to ![]() :

:

or any ![]() .

.

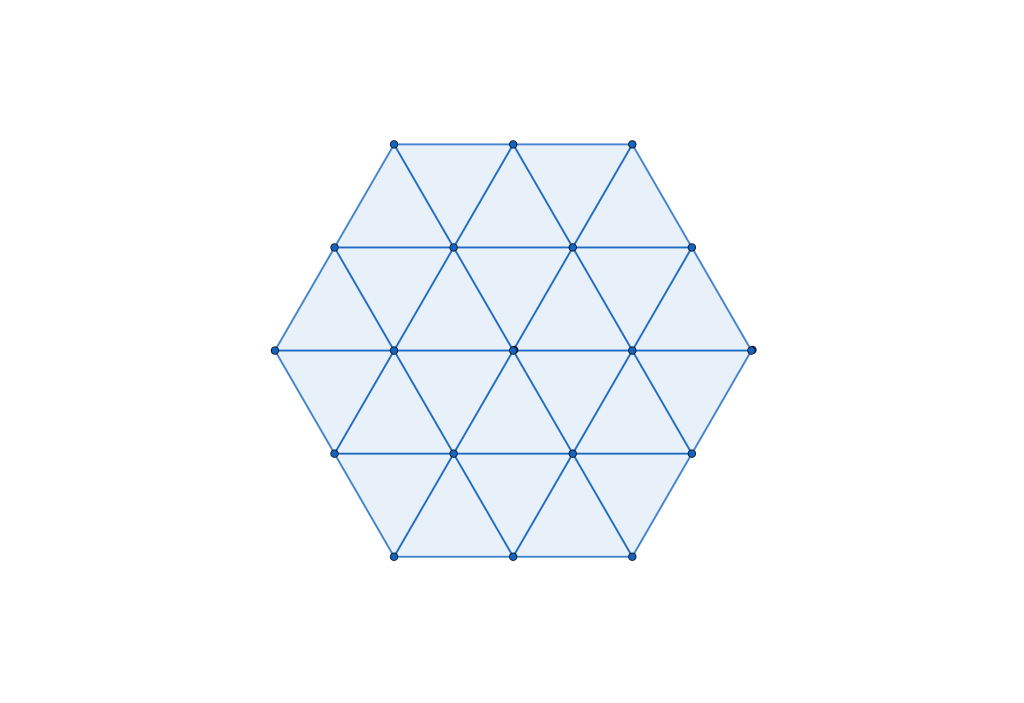

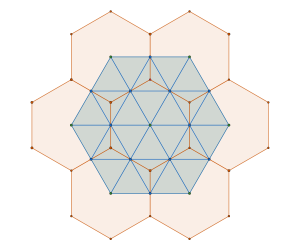

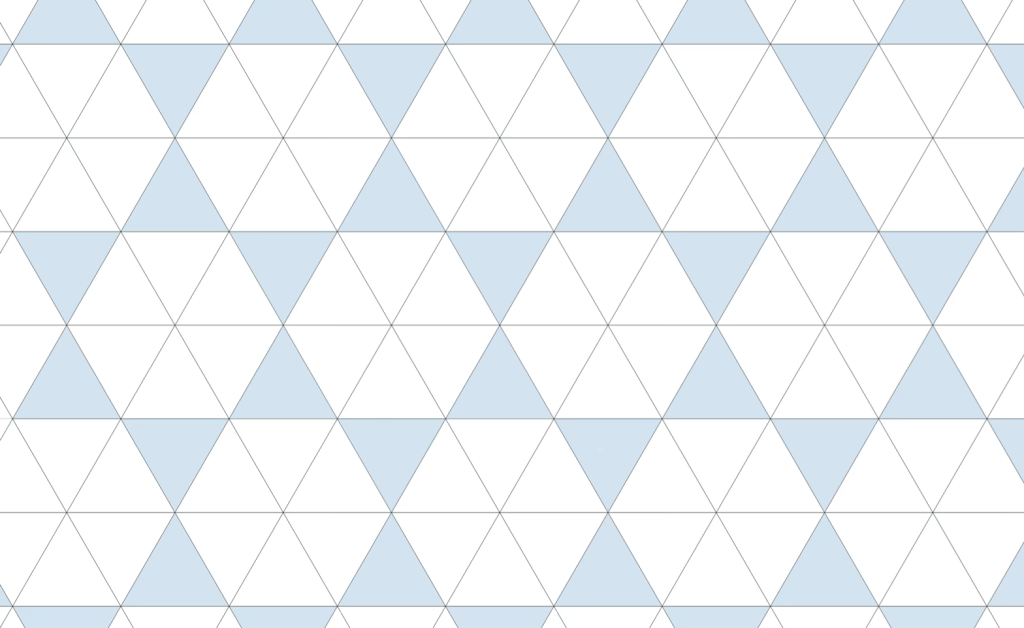

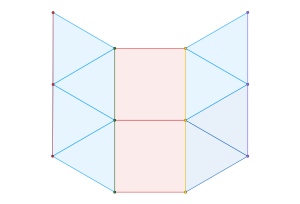

What we did is that we transformed the problem of finding molecular system minimizers into finding minimizers of a single-particle system with potential ![]() for

for ![]() , and we already know that the global minimizer is a dilated, translated, or rotated version of the triangular lattice.

, and we already know that the global minimizer is a dilated, translated, or rotated version of the triangular lattice.

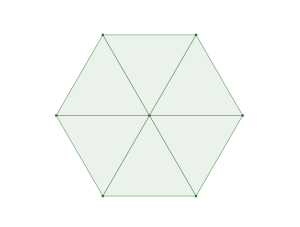

Geometrically, this transformation effectively contracts local clusters into single points, resulting in a regular triangular tiling:

Having resolved the crystallization question, let’s examine the ground states’ characteristics, starting with a natural question: Are there other possible crystal phases? (From the materials science perspective, this question is important because of Crystal polymorphism)

On one side we can view our ground state configuration as a triangular tiling because of the rigidity of the blue molecules. On the other side, because of the way we have reframed the intermolecular interactions in terms of pairwise cluster interactions we may view the ground state configuration as the triangular lattice. The connecting point of these two views are the Archimedean circle packings and their associated semi-regular tessellations.

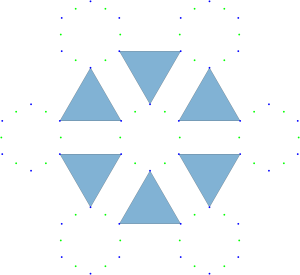

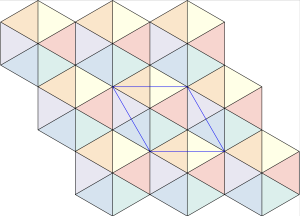

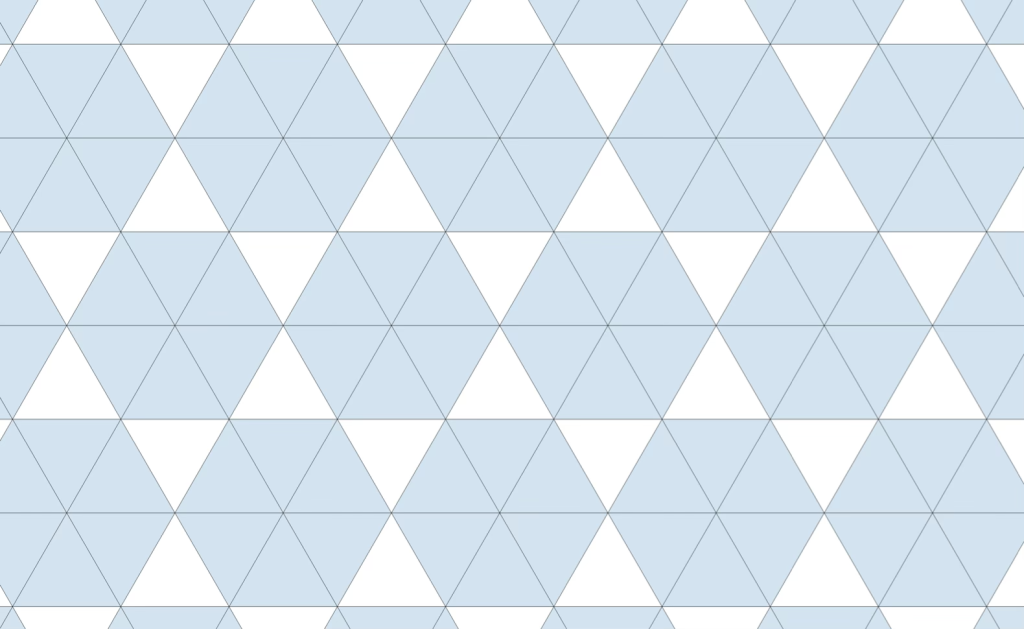

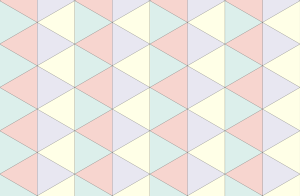

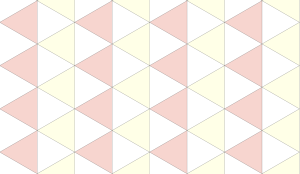

The densest packing of regular triangles is the ![]() configuration with a density of

configuration with a density of ![]() . It is, in fact, a tiling of triangles as shown below.

. It is, in fact, a tiling of triangles as shown below.

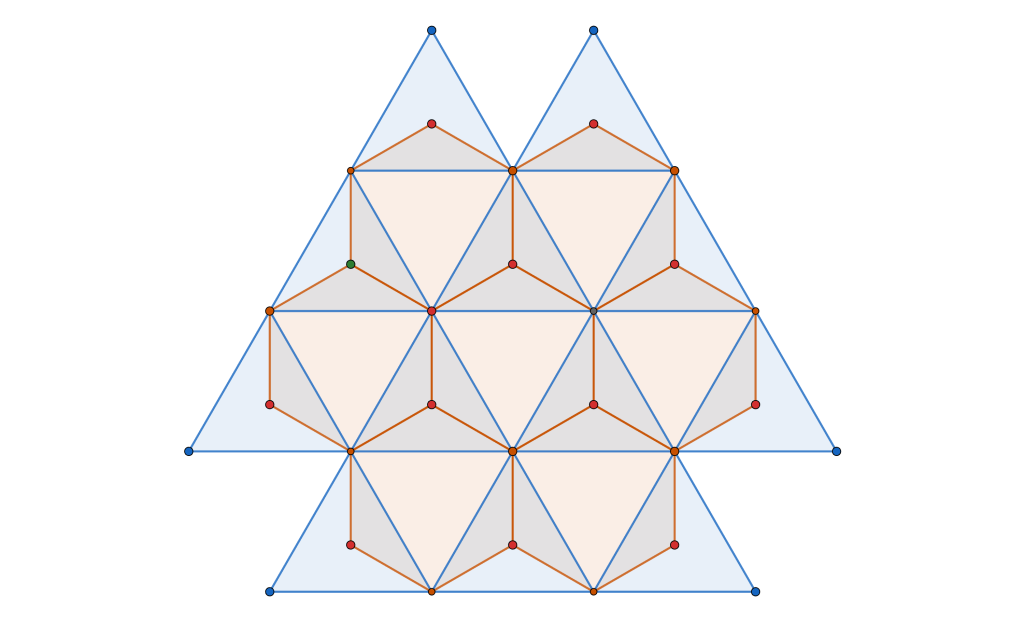

The maximal non-isomorphic subgroup of ![]() is the

is the ![]() plane group. The densest packing of regular triangles when the packing configurations are restricted to the

plane group. The densest packing of regular triangles when the packing configurations are restricted to the ![]() isomorphism class has a density of

isomorphism class has a density of ![]() and is shown in the image below.

and is shown in the image below.

This is, in fact, a consequence of removing one of the mirror symmetries from the ![]() plane group.

plane group.

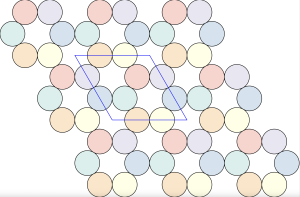

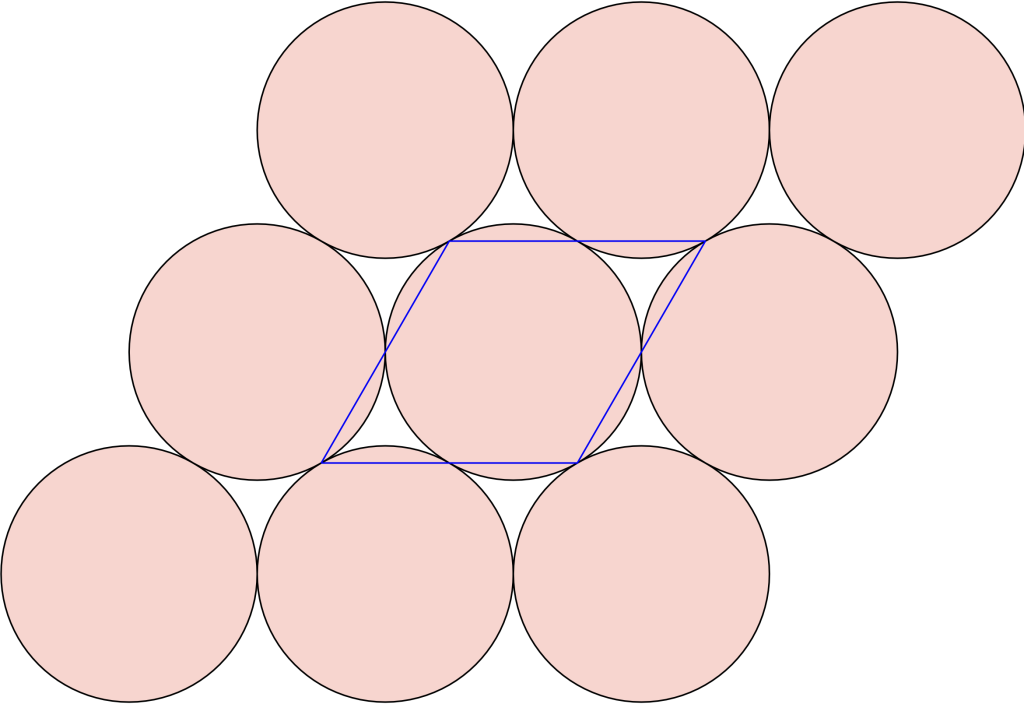

Another way to get here is to look at ![]() , the Archimedean framework

, the Archimedean framework

associated with the ![]() disc packing with packing density of

disc packing with packing density of ![]()

, and the Archimedean framework associated with the hexagonal close packed configuration of disc with density ![]()

and its associated Archimedean framework

By interlacing the hexagonal and triangular frameworks

we construct new framework. The common (blue) intersection point of the hexagona and triangular frameworks in fact define a triangular sub-tiling

and the p![]() is constructed by removing triangle tiles containing a vertex at its center of mass

is constructed by removing triangle tiles containing a vertex at its center of mass

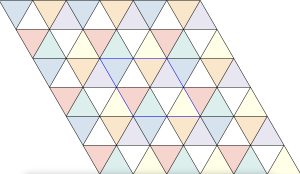

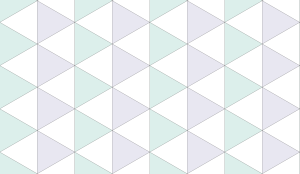

Alternatively we can create a complementary triangle packing with density of ![]() by removing tiles not containing an interior vertex

by removing tiles not containing an interior vertex

The resulting structure is sometimes referred to as the Kagome Lattice, although it is not a lattice per se.

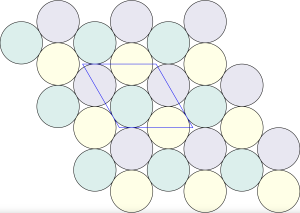

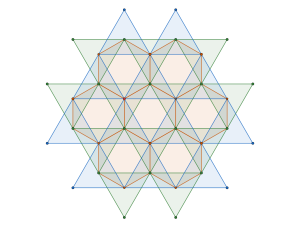

Starting from the ![]() triangle packing which is in fact a tiling

triangle packing which is in fact a tiling

and decomposing it into two complementary packings with ![]() symmetry with density of

symmetry with density of ![]()

This should come as no surprise since ![]() is the a maximal t-subgroup of

is the a maximal t-subgroup of ![]() of index 3.

of index 3.

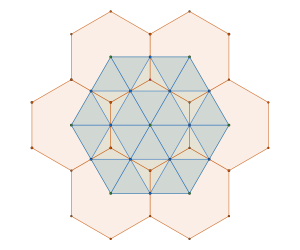

To demonstrate this point, we start again from the ![]() disc packing framework

disc packing framework

and interlace it with the triangular framework associated with ![]() packing of discs

packing of discs

in such a way that disc centers are are subsets of the hexagon vertices

and we remove one ![]() symmetry from the tiling, the one not having a hexagon vertex at its center.

symmetry from the tiling, the one not having a hexagon vertex at its center.

In fact, there are two possibilities to achieve the same result by using the triangle tiling above and rotating it by ![]() with respect to zero (center of the middle pentagon).

with respect to zero (center of the middle pentagon).

and do exactly the same thing as previously to get the second ![]() triangle tiling

triangle tiling

Combining these two triangle packings,

the ![]() symmetry of

symmetry of ![]() should be clearly visible.

should be clearly visible.

This tiling is a isomorphic to the one of the Archimedean (semi-regular vertex transitive) tilings associated with the densest ![]() packing of discs with density of

packing of discs with density of ![]()

with it’s ![]() semi-regular tiling

semi-regular tiling

These constructions are nothing new. For a comprehensive treatment of regular and semi-regular tilings, I recommend Regular Polytopes by H. S. M. Coxeter, first published in 1947. (Coxeter was the geometer who inspired M. C. Escher, which resulted in the Circle Limit I–IV series.)

Returning to our original problem of characterizing and enumerating possible Coulomb potential ground states of our molecular system, all these triangle packings represent viable local energy minima. This conclusion follows from our transformation of the intermolecular interactions into a nearly spherically symmetric “energy per cluster” potential, which preserves all symmetries of the hexagonal close-packing configuration of discs: p2, p2gg, pg, p3, and p1, as well as the rigidity of the triangular molecule.

We have classified the packings by associating each configuration with Archimedean disc packings and tessellations. The global energy minimizer corresponds to the triangular tiling and lattice, as demonstrated by Theil in “A Proof of Crystallization in Two Dimensions” (Commun. Math. Phys. 262, 209–236, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00220-005-1458-7. Since all our configurations are subsets of the triangular tessellation relative to some tiling symmetry subgroup, they are energy minimizers within their respective symmetry groups. (See Bétermin, L. “Effect of Periodic Arrays of Defects on Lattice Energy Minimizers,” Ann. Henri Poincaré 22, 2995–3023, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00023-021-01045-0.)

A property of Archimedean tessellations is that they are vertex-transitive, meaning the same number, ![]() , of regular

, of regular ![]() -gons meet at each vertex. In triangular tessellations, six regular triangles (

-gons meet at each vertex. In triangular tessellations, six regular triangles (![]() -gons) meet at each vertex. For regular tessellations like the triangular one, this follows a simple equation:

-gons) meet at each vertex. For regular tessellations like the triangular one, this follows a simple equation:

![]()

This is only for one type of polygon, but we have more types. However, we can generalize this formula to n-types of polygons:

![]()

For example, the tessellation associated with the ![]() packing of discs shown above has every vertex surrounded by

packing of discs shown above has every vertex surrounded by ![]() regular

regular ![]() -gons (triangles) and

-gons (triangles) and ![]() regular

regular ![]() -gons (squares).

-gons (squares).

Ultimately, the equation above is simply a disguised form of the Euler characteristic for plane-connected graphs induced by the vertex figure of a semi-regular tessellation.

What does this mean in the context of our molecular system?

- The vertex figure of each ground state is determined by the leading contributions to its total energy.

- In training Graph neural networks for Machine-learned interatomic potentials, learning these interactions alone suffices for ground state prediction in such molecular systems, significantly improving computational efficiency.

-

Combined with the Crystallographic restriction theorem, this formula allows us to explore possible ground state configurations based on molecular shape. In a periodic configuration, for every

, there exists at least one

, there exists at least one  such that the expression

such that the expression  holds. Thus, for any such

holds. Thus, for any such  -gon shaped molecule, the vertex figure equation has only a finite number of integer solutions. Unfortunately, in cases like the pentagon, we might need to delve into the realm of aperiodic tilings.

-gon shaped molecule, the vertex figure equation has only a finite number of integer solutions. Unfortunately, in cases like the pentagon, we might need to delve into the realm of aperiodic tilings.

Additional Notes

In this blog, we considered the existence and structure of the minimisers of a simple Coulomb electrostatic energy in the context of a model two-dimensional ionic molecular system.

Conversely, if we assume that the ground state of this ionic molecular system corresponds to the configuration of the 19 ionic clusters shown previously, then, as ![]() tends to infinity, the energy per cluster,

tends to infinity, the energy per cluster, ![]() , is essentially an instance of the Madelung constant, up to a scaling constant.

, is essentially an instance of the Madelung constant, up to a scaling constant.

Furthermore, the local cluster configuration ![]() defines a configuration polygon and the solutions of

defines a configuration polygon and the solutions of ![]() for

for ![]() and

and ![]() correspond to ground states of the configurational energy constrained by a constant average concentration. For more details, see Sanchez, J. M., & De Fontaine, D. (1981). Theoretical Prediction of Ordered Superstructures in Metallic Alloys. in O’Keeffe, M. & Navrotsky, A. (Eds.). Structure and Bonding in Crystals Volume II, 2, 117-132.

correspond to ground states of the configurational energy constrained by a constant average concentration. For more details, see Sanchez, J. M., & De Fontaine, D. (1981). Theoretical Prediction of Ordered Superstructures in Metallic Alloys. in O’Keeffe, M. & Navrotsky, A. (Eds.). Structure and Bonding in Crystals Volume II, 2, 117-132.

Moreover, the treatment of ionic crystals using the interstitial voids of eutactic structures, as detailed in the book Crystal Structures: Patterns and Symmetry by Michael O’Keeffe and Bruce G. Hyde (first published in 1996 by the Mineralogical Society of America and recently reprinted by Dover Publications), provides additional context for our ionic molecular crystal model. In a sense, the instance considered here can be regarded as an extension of the description of monoatomic ionic compounds to ionic molecular systems.

Additionally, Madelung energy, a quantity related to Madelung constants and recently applied in the context of organic salts by Izgorodina, E. I., Bernard, U. L., Dean, P. M., Pringle, J. M., and MacFarlane, D. R. (2009) in The Madelung Constant of Organic Salts, Crystal Growth & Design, 9(11), 4834–4839, is somewhat reminiscent of our ionic molecular crystal model.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Vanessa Robins for pointing me to towards the quantities called Madelung Constants and to the work of Michael O’Keeffe during our discussion of this blog post at the ICERM Geometry of Materials workshop.